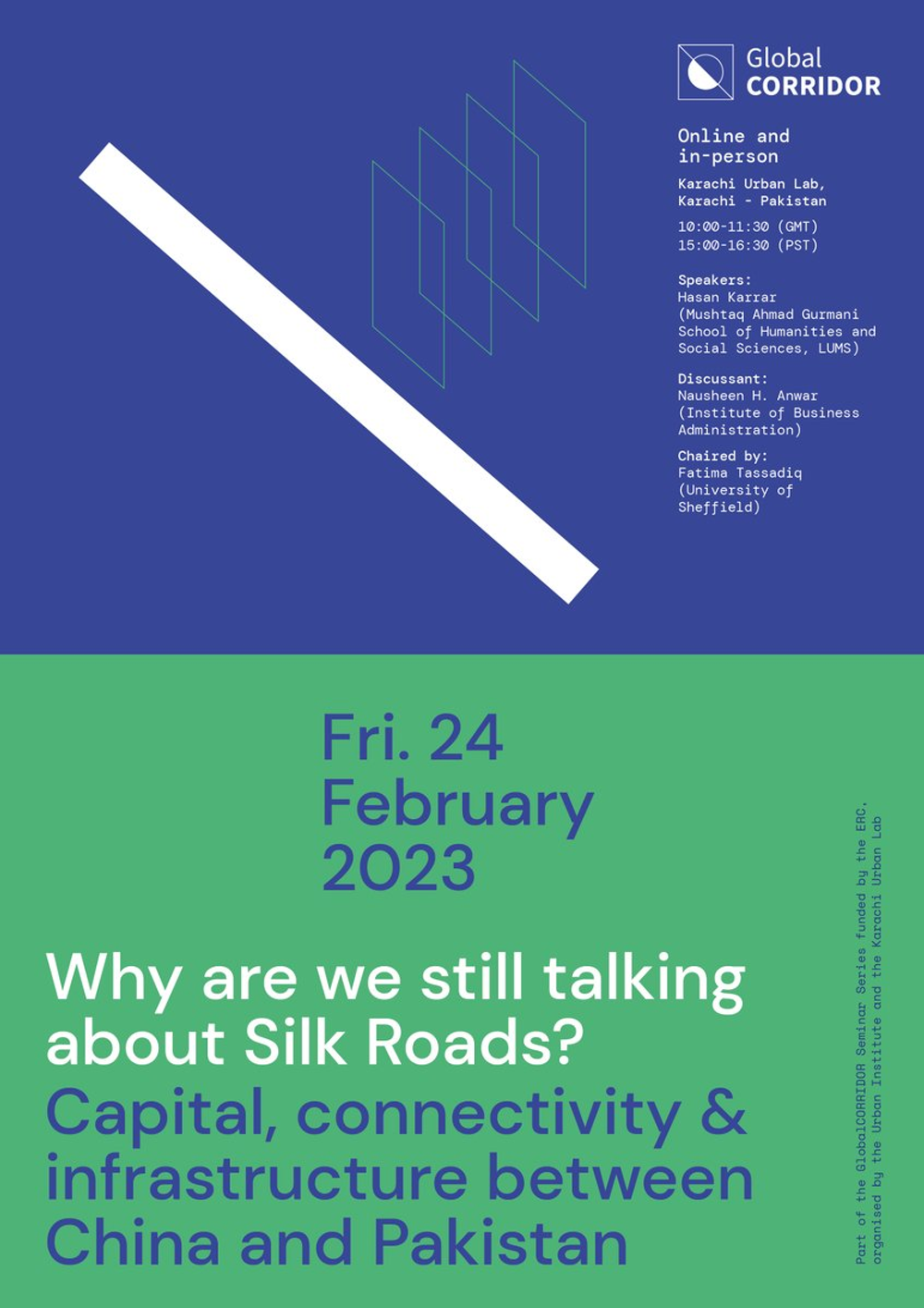

Why are we still talking about Silk Roads? Capital, Connectivity & Infrastructure between China and Pakistan

Speakers

Looking at the long association between Pakistan and China, this talk explored the utility of the trope of the Silk Road to understand the relationship between the two countries and explored other ways of thinking about proximity and infrastructural development.

Professor Karrar began by briefly tracing the history of the use of ‘Silk Road’ to frame geopolitical relations in Asia. The various iterations of the trope have emerged sequentially over time. It was originally proposed by Richthofen in the late nineteenth century and emerged out of the imperial project in Asia. At the time it was used to animate visions of a railroad across Asia – railways being the apex of European modernity at the time. After the Bandung conference in 1955, the trope was appropriated by China and Pakistan and used to frame solidarity between non-aligned countries that enjoyed proximity with China’s geo political interests. In its current formulation Silk Road serves as a malleable spatial imaginary used to articulate affective and material ties between Pakistan and China.

Professor Karrar then moved on to consider connectivity as affect, and as an ephemeral and malleable concept. The curious aspect of the affective ties between the two countries is that the vast majority of people in Pakistan and China have never met or interacted with someone from the other country. Affective ties between the two countries as mobilized by political leaders are also marked by a discord: the Pakistani leadership has been much more effusive in its invocation of affinity between the two countries than their Chinese counterparts. Historically, this connectivity has also been ephemeral: colonial archives show evidence of trade between colonial northwest India and Xinjiang as well as incidents of border closing. Contemporary BRI maps and images show how visions of connectivity between different host countries and China are malleable and easily adapted to conform to different political visions.

The third part of the talk explored the ways in which movements of capital underpin the relationship between the two countries. Professor Karrar identified three ways in which capital animates Pak-China collaborations: capital as rent where Pakistan extracts rent on commodities moving through the country; capital as speculation or the ‘Dubai model’ where the state and private actors create an enabling environment for real estate investment and land speculation; and finally capital as finance or the ‘Schengen model’ where an enabling environment for industrial capital is created to set up manufacturing units geared towards export production. In the case of CPEC it is capital in its speculative role in the real estate market that is dominant and appears to be driving many of the joint projects between the two countries.

The lecture closed with a discussion of the role of infrastructure. While infrastructural improvement under CPEC has increased the volume and value of goods crossing the border, it has cut off local small traders who find it increasingly hard to navigate greater securitization in the area. It is also important to note that several CPEC projects are actually initiatives that predate the collaboration between the two countries and have been brought under the CPEC umbrella through negotiations by Pakistani bureaucrats and politicians. Consequently, CPEC instead of being a top-down venture in Pakistan is a contested and patchworked terrain of infrastructural development.

Professor Anwer in her response noted the importance of moving between scales when it comes to studying the affective underpinnings of Pak-China relations. Drawing on her research on the construction of coal power plants in Thar, she talked about the visceral anti-China sentiments that are often expressed by the locals. She also discussed the significance of ‘strongmen’ in the realization of CPEC projects. Finally, she complicated notions of heartlands and hinterlands that animate discussions of infrastructure corridors by pointing out how former hinterlands like Thar have seen unprecedented urbanization and reverse migration due to the opportunities created by the coal power plants. Comments and questions from the audience prompted a discussion on the role of the Pakistan military and new multi-lateral institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank in mega projects in the region. Participants in the conversation also drew attention to older more discreet corridors that have informed Pakistan’s relations with its neighbours as well as the impact of contemporary CPEC projects on local populations, especially those in Gilgit Baltistan and Gwadar.